How Art and Science Collide at the CERN Physics Laboratory

“Knowledge is limited,” Albert Einstein once said, “imagination encircles the world.” A new program at the CERN physics laboratory, home to the Large Hadron Collider, takes Einstein’s words as their mantra. Collide@CERN hopes to invite artists of all disciplines to work as artists in residence at the laboratory, where they can both be inspired by the science and inspire the scientists to make new discoveries. While protons collide in the machinery at unimaginable speeds and perhaps reveal some of the secrets of the universe, the artists and scientists will collide in ways that may help make some of those secrets more intelligible to the human imagination. With this initiative, the chasm between the arts and the sciences may finally be bridged.

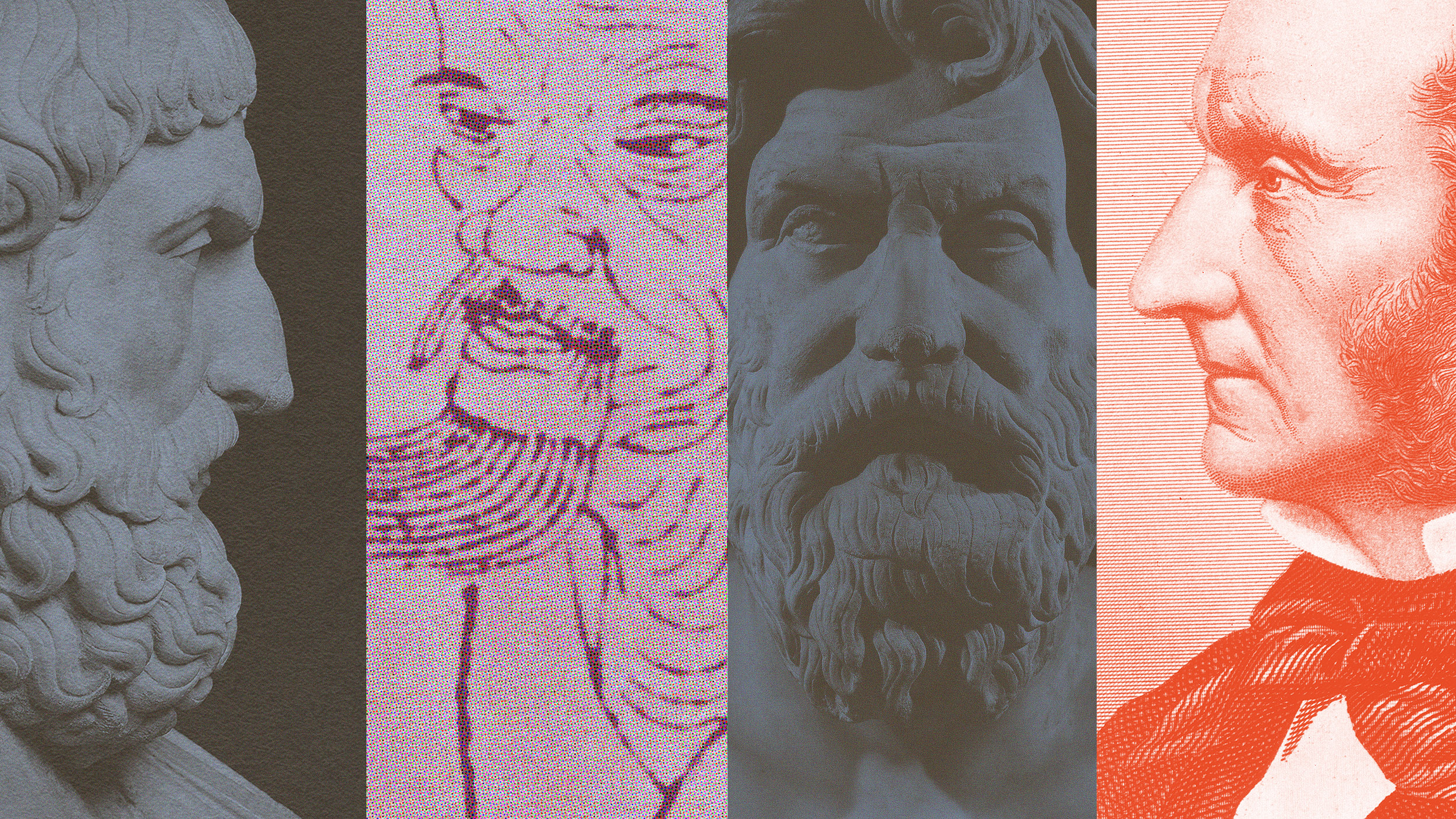

As reported in a recent issue of The Art Newspaper, the first part of the program will focus on digital arts, while the second half will center on performance and dance. Artists can apply online for the three-month residency and stipend of €10,000 that comes with the chance to be mentored by the CERN scientists and given a unique opportunity to experience the cutting edge of physics from the inside. In that same issue, Ariane Koek, head of international arts development and the arts programme at CERN, explains that arts/science, aka “sciart,” is currently the hot international art movement of the moment, partly “driven by new funding possibilities from science in the current arts cash crisis.” Koek sees another crisis behind the sciart trend as well—“a reduction in the wonder of creativity itself, and the question of who controls it and how. Creativity, and where it comes from, is one of the last great human frontiers, and one over which we have little control, cash crisis or no cash crisis.” CERN has already inspired many artists over the years (as shown in their online gallery), including Simon Norfolk’s 2008 CERN Series, which finds a complex beauty in the architecture of the laboratory and collider.

It’s good to know that people like Koek carry enough influence in the science world to bring the world of the arts into that circle. For too long the “hard sciences” with their rigor and exactitude snubbed the “softer” disciplines and their ambiguity and inexactitude. Of course, Thomas Kuhn’s landmark 1962 book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions argued convincingly that paradigm shifts arose not from pure evidence but from a combination of mounting evidence and a social and cultural willingness to give up the previous theory. Kuhn’s ideas have gained acceptance over the decades, but the bias lingers on in many ways. The CERN arts program will go a long way in ending that bias for good.

Koek’s call for a solution to the creativity crisis in an artistic invasion of CERN reminded me of a chapter from Henry Adams’ The Education of Henry Adams. In “The Dynamo and the Virgin,” Adams writes, “On one side, at the Louvre and at Chartres [Cathedral],… was the highest energy ever known to man, the creator four-fifths of his noblest art, exercising vastly more attraction over the human mind than all the steam-engines and dynamos ever dreamed of.” Adams saw the power of Christianity behind the great cathedrals as more dynamic than any technology made by man. The CERN art program threatens to prove Adams wrong. Perhaps today’s technology probing the fundamental secrets of the universe—what Stephen Hawking once called “the mind of God”—can be the new force for human creativity. Perhaps the Large Hadron Collider is the cathedral of the 21st century.

[Image:Simon Norfolk. From the CERN Series, 2008.]