How Vandalizing the Tate Rothko Is Desecrating a Grave

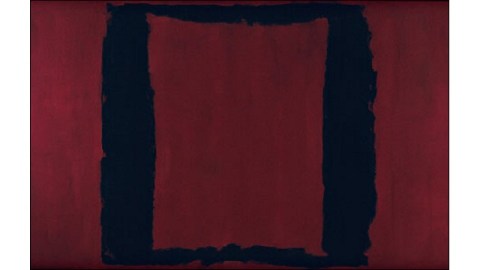

Upon hearing news of the vandalizing of Mark Rothko’s 1958 painting Black on Maroon (shown above), a part of me cried out in pain. Few artists cut to the core of what it is to be a human being as Rothko, as testified by the enduring appeal of his paintings, which remain as hypnotic and personal as they were when he took his life more than 40 years ago. A vandal calling himself Vladimir Umanets tells the BBC that he attacked the Tate’s prize painting not as a vandal but as an “artist” carrying on the mission of Duchamp under the theoretical banner of “Yellowism.” Vladimir Umanets, whose name (thanks to Holly Knowlman’s detective work on the Yellowism Facebook page) is an anagram for “I’m true vandalism,” demonstrates “Yellowism” only as a sign of cowardice—an individual or group masquerading as an art movement by damaging the works of the past. Tagging Black on Maroon with a graffiti pen, however, isn’t just art vandalism. In this case, it’s the desecration of a grave.

“Umanets” walked into the Tate Modern gallery housing Rothko’s Seagram Murals, which the artist himself donated to the museum in 1969, and marked the corner of Black on Maroon with a graffiti pen. The words “Vladimir Umanets ’12 A Potential Piece of Yellowism” ran wetly down the canvas as shocked visitors tried to find a guard. The assailant allegedly admired his handiwork for a moment before leaving the scene of the crime. British police are currently searching for the attacker. Hrag Vartanian at Hyperallergic gathers together all the gory details, along with (as of this writing) fourteen updates, including a statement by Kate Rothko Prizel and Christopher Rothko, the artist’s children, saying that they “are heartened to have felt that embrace again in the outpouring of distress and support that we and our father have received both directly and in public forums.”

As you can see from Vartanian’s reporting, much of this story, as pretty much any story today, played out in social media, from tweets by witnesses to mining of Facebook pages for information about the group. As you may have noticed, I’ve refrained from providing links to any of the Yellowism group pages. I refuse to acknowledge, encourage, and reward the people who committed this crime. If they want attention, they have it—from the police. What I want to focus on, and celebrate, is the art they’ve drawn out attention to once more.

When The Four Seasons restaurant prepared to open in the newly constructed Seagram’s Building in New York City, they commissioned Rothko to paint a series of works to hang in the restaurant. Although Rothko was no stranger to commissions, the Seagram Murals project confounded him. After seeing the restaurant’s interior personally, Rothko refused to complete the project, believing that his paintings were too important and meaningful for the commercialized setting of an eatery. Rothko kept the murals in storage until 1968, when he agreed to donate them to the Tate. The murals arrived in London for display on February 25, 1970, the same day that Rothko’s assistant found the painter dead, having committed suicide in front of his kitchen sink.

The overpowering drama surrounding the paintings and their new home stars in Simon Schama’s installment of The Power of Art featuring Rothko and, specifically, Black on Maroon. Rather than reading the murals as an oversized suicide note, Schama sees them as a love letter to humanity, a user’s guide to the cosmos. In the final scene of the episode (which is also the last in the series and, thus, Schama’s “final word”), Schama’s says that the murals are “meant not to keep us out, but to embrace.” (Go 3 minutes into the video here to get the full effect.) The viewer stands right there beside Schama before the immense murals (which, like all Rothkos, must be seen in the flesh to be believed, felt, and understood) in the Tate gallery, just as the vandal later would, but feeling much different emotions and thinking much different thoughts. “Can art ever be more complete, more powerful?” Schama asks, before answering, “I don’t think so.” I don’t think so either. Perhaps this act will bring Rothko into the minds and hearts of more people, but it’s a shame that his work and his memory had to be trampled upon in the process.

[Image: Mark Rothko. Black on Maroon, 1958.]