More Gritty (Fishy?) Truth

So my “True Grit” post got a lot of response (unfortunately not below) on Facebook and by email and all that–mostly critical. One particularly astute critic–Ken Masugi–accused me of being in the “bad company”of that celebrated postmodernist-wrongly-understood Stanley Fish.

According to Masugi, Fish manages to make the film (and novel) both religious and nihilistic. It celebrates the religious devotion of Mattie while making clear that there’s no reality that corresponds to it. Postmodernists like Fish say that people have narratives by which they make sense of the world, but there’s no objective way of privileging one narrative over another. So Fish might be accused of ruining liberal education through saying the great teachers can’t, in fact, tell the truth about who we are and what we’re supposed to do.

If that’s so, administrators respond, then real education comes from those can back up what they teach with measurable, quantitative results, results that lead to the real production of power. The sciences are real, the humanities are, finally, edifying baloney that help us get through our, in truth, deeply meaningless lives. Fish often writes in favor of being religious, but at the expense of showing that “religious truth” is a self-deceptive oxymoron.

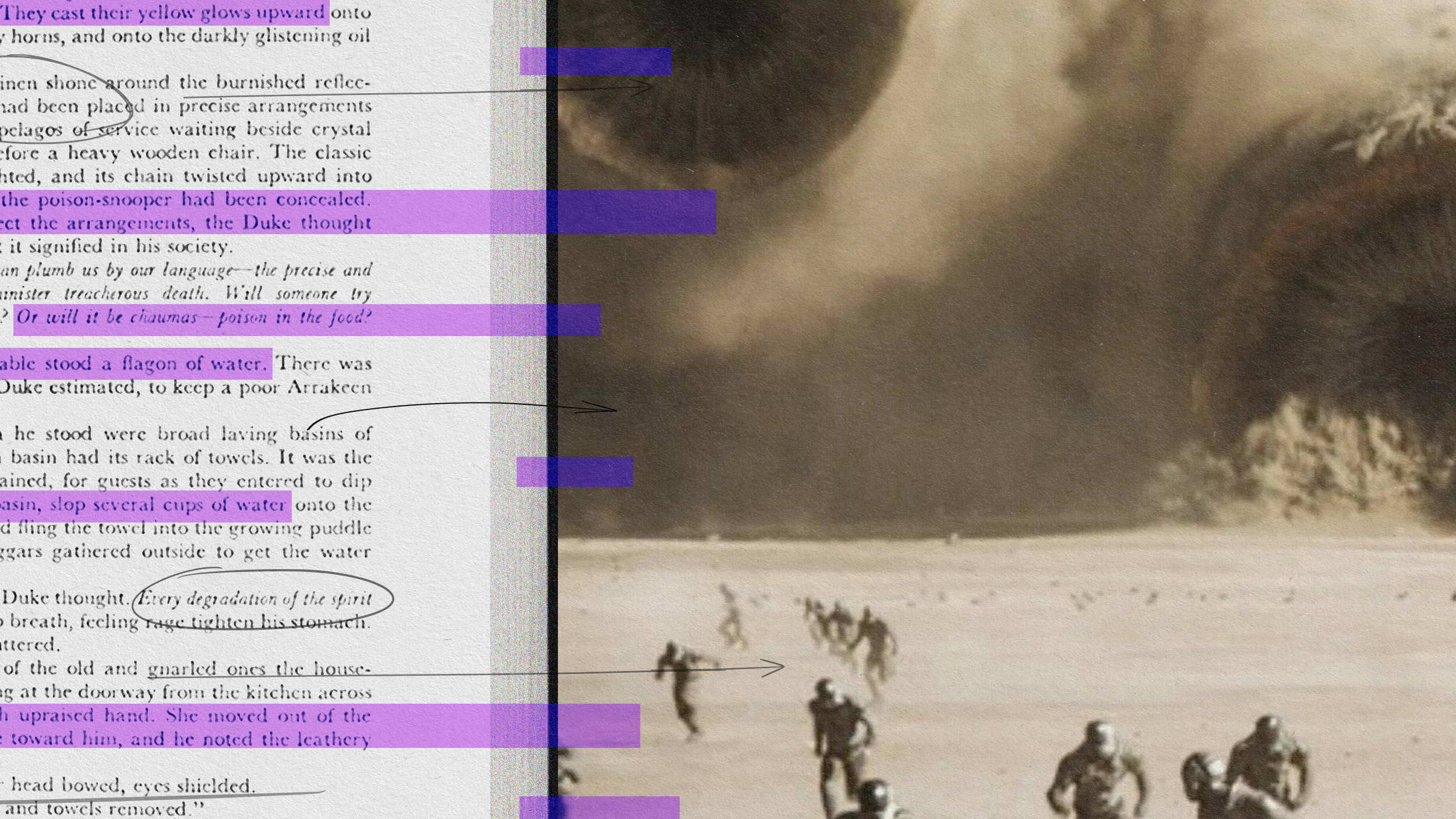

Let me save Fish from his nihilism by giving a different interpretation of some of the facts about the film and the novel he so perceptively notices: Mattie is a very clever and spirited young lady, all about “rational control.” She wants to make the world makes sense. She thinks she’s smart enough and resolute enough to employ the law and contracts to gain fearful and mercenary control over dumber (but physically stronger and more capable) and emotionally weaker men to achieve justice.

She achieves enough success that she forgets the words she mouths at the film’s beginning about grace being a limit to human merit or retributive justice and pride.

In truth, she gradualy loses control of her situation or over men in the lawless “state of nature” of the wild Indian territory. She becomes more dependent on the natural strength and skill graciously given her by increasingly honorable (or nonmercenary) men. At the moment of her greatest triumph–shooting the man who killed her father, she falls into a pit of snakes.

That great moment, of course, was pretty fortuitous, not mostly her own doing. It was the two men in her life who won a most noble and quite improbable victory over the outlaws–a victory certainly inspired by her but not controlled by her. Mattie, in her vanity, almost deserves to fall into a pit of snakes, where she will surely perish on her own.

But she is rescued by Rooster, who graciously–or completely voluntarily or animated by some mixture of nobility and love and at great risk to himself–rides her to a doctor who can save her.

So Mattie was saved by grace: Not the grace of God in any obvious sense, but by the gracious act of a free man that was more than mere charity. Mattie had forgotten that she is a creature–a personally dependent being. It’s impossible to make the world make sense all by oneself. But what (who) saved her was no random act in a merely chance-and-necessity universe.

The least we can see is that Chistian humility is a realistic corrective to pagan–maybe Stoic–pride. But does humility–or recognition of personal, relational limits to our individual freedom–obliterate the greatness of human individuality? No, the greatness of Mattie and the noble warriors who won a seemingly reckless victory over evil outlaws still stands.

I could qualify this interpretation in many ways. But let me conclude that the film, maybe against the intention (for all I know) of the famously nihilistic filmmakers, does display some realistic (and so somewhat Christian) psychology. To some extent at least, the Bible does tell the truth about who we are.

Does any of this depend on the real existence of personal God? Not in the eyes of the Coens, at least.