Errol Morris: Disbelieving is Seeing

“Cinema is truth 24 frames per second,” the French new wave director Jean Luc Godard famously said. Not so, said German filmmaker Michael Haneke: “Film is lies 24 times a second to serve the truth.”

Whether film is always a manipulation or not, we have grown to expect that in the documentary cinema of the award-winning filmmaker Errol Morris, the truth will somehow win out. And in Morris’s films, the truth has profound, real-life consequences. An innocent man is sentenced to death for the murder of a Dallas police officer (The Thin Blue Line). But then the real killer confesses at the very end of the film. Cinematic, not to mention real-life justice, is served.

The case of Jeffrey MacDonald, the subject of Morris’s latest book, A Wilderness of Error, is considerably more complicated. In 1979, a jury found MacDonald guilty of murdering his family, and the matter of his guilt or innocence has been hotly debated ever since. Even Sarah Palin has weighed in (more on that later).

Here is a trailer (in 3D) for Morris’s book:

What’s the Big Idea?

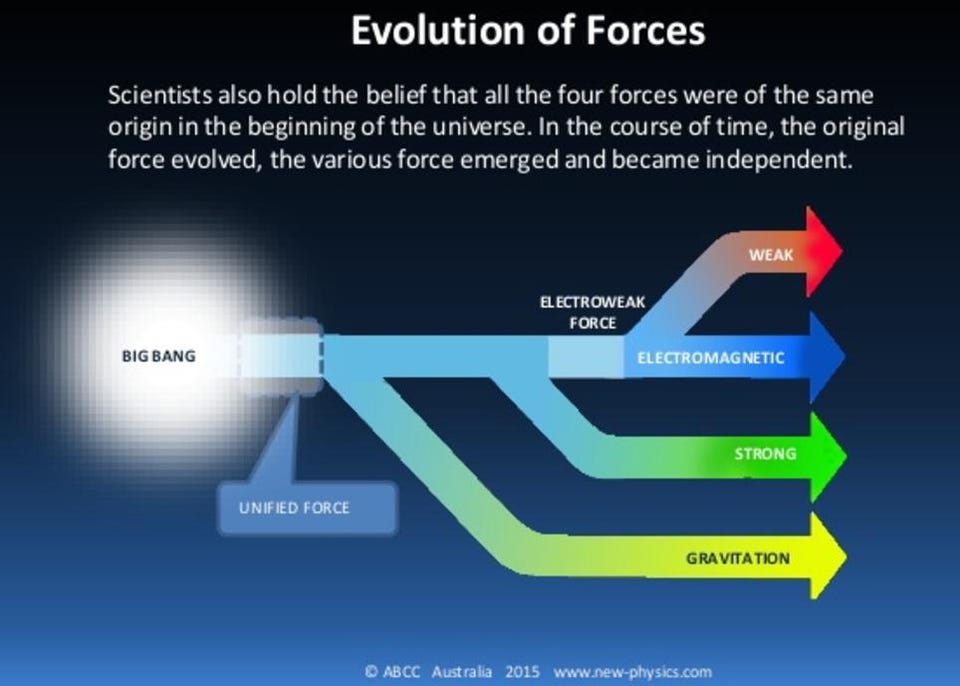

“We see on the basis of what we believe, not the other way around,” Errol Morris told Big Think in a recent interview. This is confirmation bias. In other words, our relationship to the truth is never neutral nor “value-free,” Morris says. The police walk into a crime scene and hastily construct a narrative to explain what they see. Once this “theory” has been firmly established in their minds, the actual evidence “becomes invisible.”

Watch the video here:

What’s the Significance?

Confirmation bias is certainly not limited to police work. In fact, confirmation bias might be evident in the reactions to Morris’s book. Here’s the quick backstory.

Jeffrey MacDonald granted the journalist Joe McGinniss full access during his trial in 1979, believing that McGinniss would exonerate him. However, that was not the conclusion that McGinniss arrived at in his best-selling true crime book, Fatal Vision, published in 1983.

In the spring of 2010, McGinniss moved to Alaska to write an unauthorized biography of Sarah Palin. He even rented a house next door to Palin’s Wasilla home. The book that resulted was The Rogue: Searching for the Real Sarah Palin, which was heavily criticized by the Palins but also by many “lamestream media” critics who objected to McGinniss playing fast and loose with the truth.

Here’s where our story comes full circle. Errol Morris’s book received an enthusiastic review from Sarah Palin, as it presented a different conclusion — that MacDonald is most likely innocent — than McGinniss’s account. “Apparently, falsely convicted men don’t make for good books,” Palin wrote. “McGinniss decided it was a better story to agree with the jury.”

Did Palin draw this conclusion due to a confirmation bias (McGinniss lied about me so he must have lied about MacDonald) or was she convinced of MacDonald’s innocence after reading Morris’s book? It’s anyone’s guess, but Morris was asked this question. Does he think Palin read his book cover to cover? His response: “Somebody did.”

Image courtesy of Shutterstock

Follow Daniel Honan on Twitter @Daniel Honan